Why the Federal Reserves’s balance sheet will not go back to pre-GFC levels

In this article, we discuss why the demand for bank reserves is so much higher today and why bank regulation prevents bank reserves from going back to pre-GFC levels.

The Federal Reserve’s balance sheet is a heavily discussed topic. I am constantly reading on CNBC, Bloomberg or X that

“The Fed is financing the US government!”

“The Fed is manipulating bond markets!”

“Everything was so much better pre-GFC when the Fed’s balance sheet was smaller!”

While there certainly is truth to the first two bullet points, I wanted to take a more nuanced look at the third bullet point. Can the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet even shrink back to pre-GFC levels? I would argue that it cannot - purely from a bank reserve standpoint. Let’s dive in!

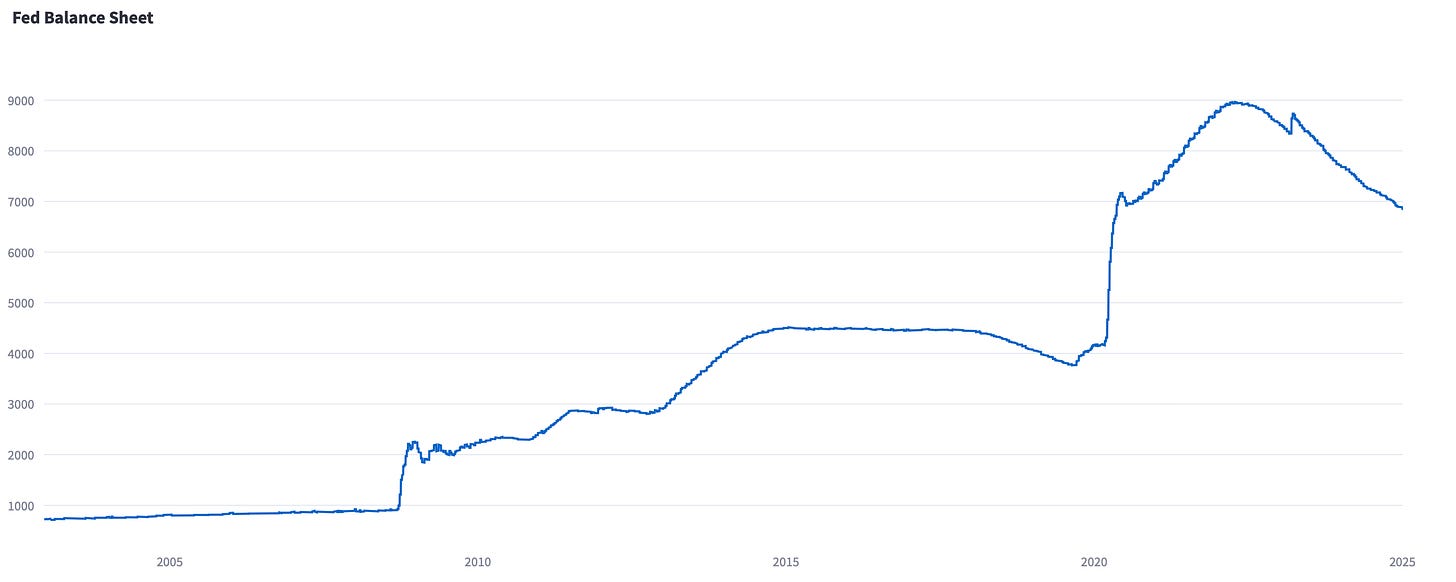

The below chart shows the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet. In January 2006, the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet was 830bn USD. Today, it is 6.8tn USD.

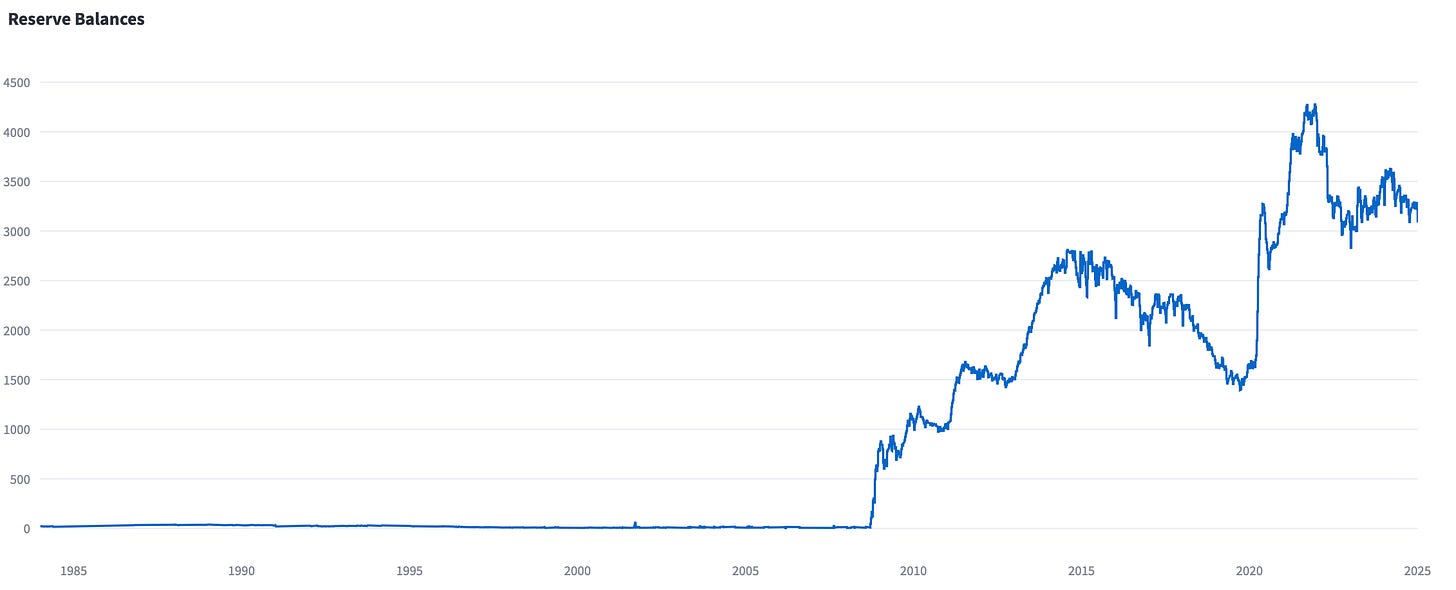

The chart for bank reserves looks even scarier! Pre-GFC, bank reserves were merely 10bn USD. Today, they are 3tn USD.

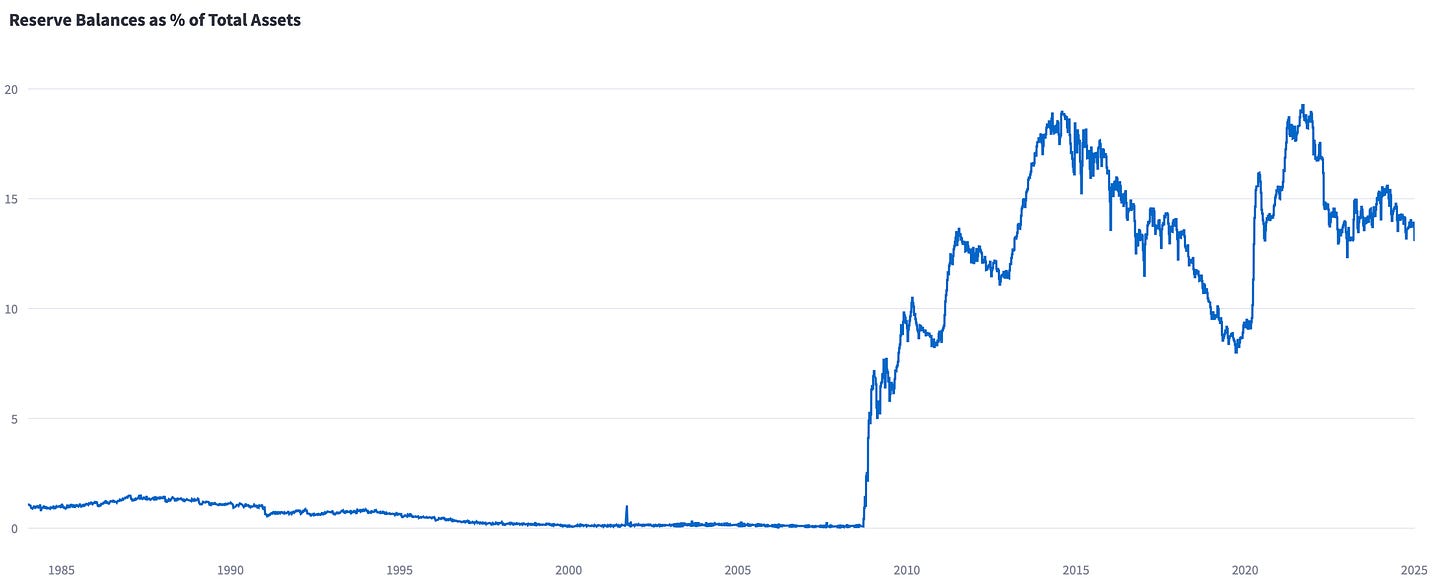

Have you ever asked yourself why bank reserves are so much higher now than pre-GFC? Even if we express bank reserves as a percentage to banks’ total assets, it seems like banks hold much more reserves today than pre-GFC. Bank reserves as a percentage to banks’ total assets are 13% right now.

Bank reserves are crucial for banks to meet their daily operational needs, like settling transactions and meeting withdrawal demands. Just as oil lubricates the parts of an engine to reduce friction and allow smooth operation, bank reserves lubricate the financial system, ensuring that transactions between banks happen smoothly.

But does the banking system really need that much more reserves today? No. The banking system always needed reserves. They just did not appear on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet in the form “reserve balances”.

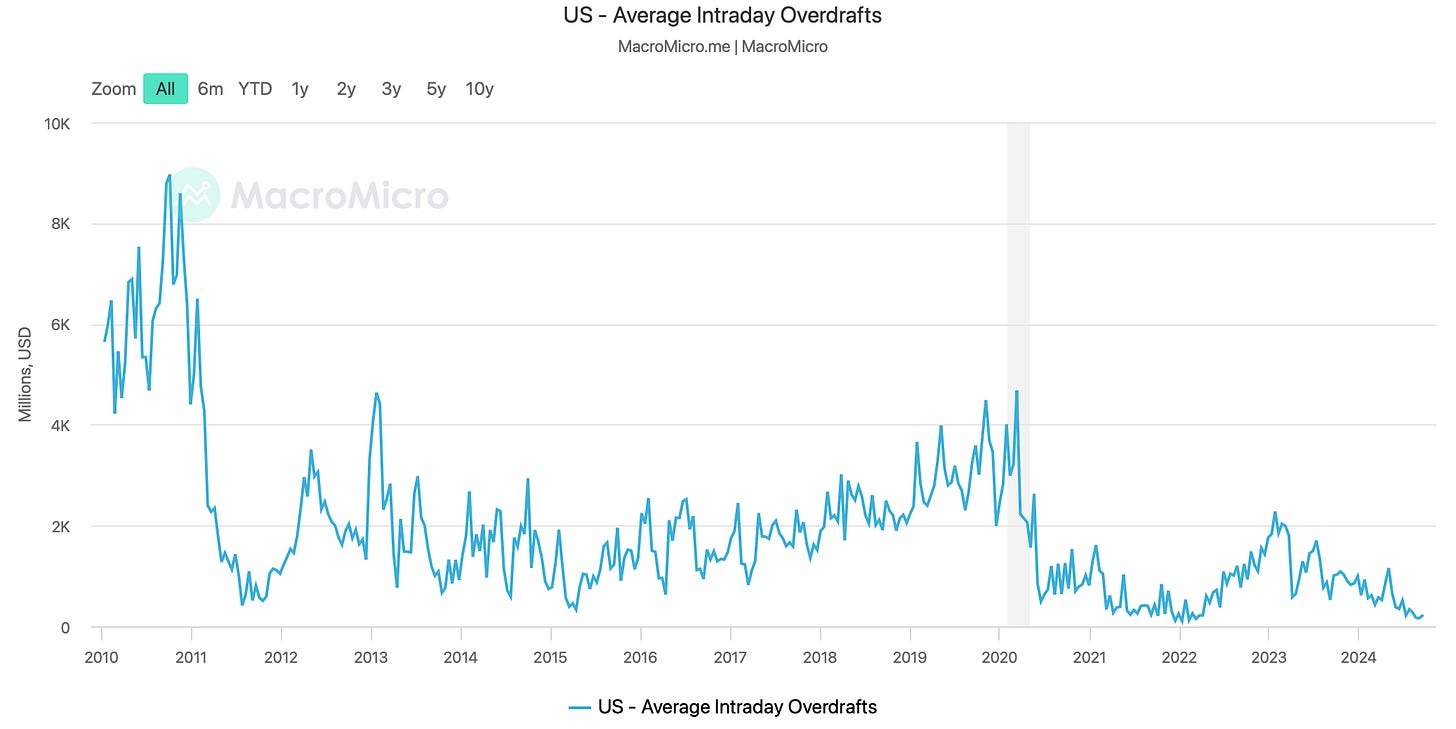

Pre-GFC, banks took advantage of intraday overdrafts at the Federal Reserve. You can compare intraday overdrafts to credit cards. When you need cash, you can borrow money on your credit card. Similarly, banks borrowed lots of cash from the Federal Reserve intraday to settle transactions.

Unfortunately, the chart below only goes back to 2010. But intraday overdrafts were much higher during the GFC. In Q2-2008, average intraday overdrafts were 71bn USD. Note, we are talking about average, not peak, intraday overdrafts here. That means banks borrowed on average more than 71bn USD intraday from the Federal Reserve. Peak overdrafts, which reflect the actual need from the banking system to settle transactions, are even higher.

Why were intraday overdrafts so much higher pre-GFC and why are they so low today? Pre-GFC, banks were not incentivised to hold reserves. If a bank held reserves at the Federal Reserve, they did not earn any interest on them. Maybe not on purpose, but banks were discouraged from holding reserves at the Federal Reserve.

Today, this is different. Banks earn interest on reserve balances (IORB) on reserves at the Federal Reserve. IORB is currently 4.40%, so 15bps above the lower bound of the Fed funds range.

Why did regulators change their opinion? When the GFC hit and regulators took a closer look at banks, they did not like that banks were heavily reliant on the Federal Reserve and could not meet cash outflows themselves.

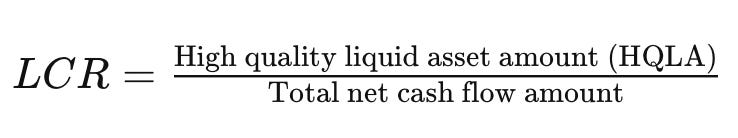

The introduction of a positive interest rate on reserve balances at the Federal Reserve was just one major change to incentivise banks to hold bank reserves. Another major change in banking regulation was the liquidity coverage ratio (LCR). The liquidity coverage ratio requires banks to always keep enough high quality liquid assets (HQLA) on the balance sheets to meet cash outflows in a 30-day stress scenario.

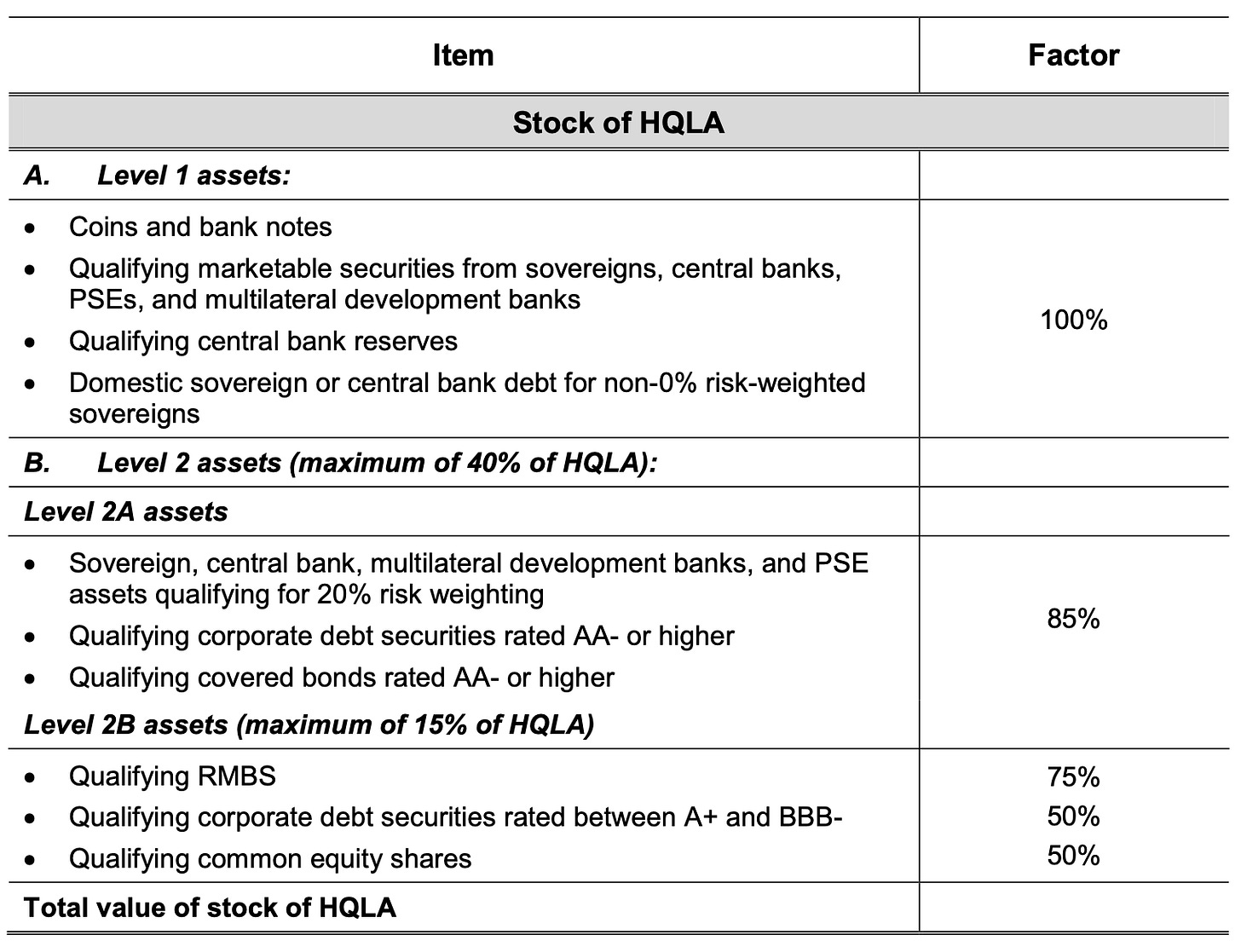

The following example explains how the HQLA stock is calculated. Level 1 assets, such as bank notes, coins, or bank reserves contribute with 100% to the HQLA buffer. Assets of lower quality (less liquid, more volatile, lower credit rating, etc.) fall into lower tiers such as level 2A and level 2B assets. If a bank owns 100mm USD of “qualifying residential mortgage-backed securities” (= level 2B), they contribute with 50%, i.e., 50mm, to the HQLA stock.

The liquidity coverage ratio requires banks to always keep more HQLA stock on the balance sheet than cash outflows in a 30-day stress scenario. I will not detail how cash outflows are calculated, but as an illustrative example: if a bank has “stable deposits” on the balance sheet, in a 30-day stress scenario 5% of these deposits are assumed to be withdrawn. Now you can add all other cash outflows, such as upcoming maturities in the next 30 days, unsecured wholesale funding, and so on and you will end up with the total assumed cash outflows in a 30-day stress scenario.

The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) was introduced as part of the Basel III framework. The final version of the LCR standard was published by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) in January 2013, but the implementation across all jurisdictions took multiple years.

Banks did not have to hold this much HQLA on the balance sheet pre-GFC. Nowadays, the demand for bank reserves on the balance sheet is much higher as bank reserves contribute with 100% to the HQLA buffer.

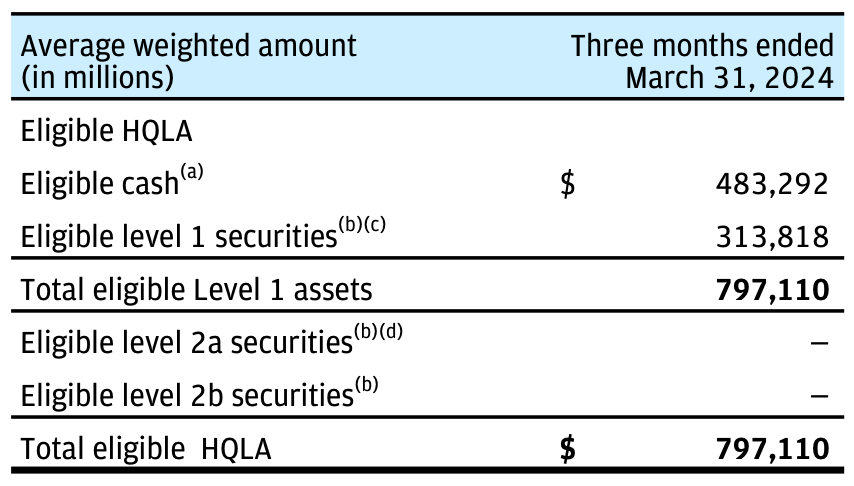

The below table shows the HQLA buffer from JP Morgan in March 2024. More than 60% of the HQLA stock is eligible cash, which is mostly bank reserves. Truthfully, JP Morgan is one of the more conservative banks out there, but it still shows you the importance of bank reserves in banks’ HQLA stock.

Let’s summarise:

Banks are incentivised to hold reserves at the Federal Reserve because they earn interest on reserve balances (IORB).

Regulators do not want banks to rely on intraday overdraft anymore to settle transactions and meet cash outflows.

The liquidity coverage ratio requires banks to hold large HQLA buffers. Bank reserves contribute with 100% to HQLA buffers.

Bank reserves cannot go back to pre-GFC levels. In fact, if you assume loans on banks’ balance sheets will grow roughly in line with GDP, then cash outflows in a 30-day stress scenario will also increase. That means banks will have to keep more HQLA stock on their balance sheets. As bank reserves are a significant part of HQLA buffers, demand for them will increase over time.

Bank reserves are roughly 40% of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet today. If the demand for reserve increases over time, then reserves on the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet will grow. You can argue about the SOMA portfolio, i.e., the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings. But bank reserves are a pretty straightforward story.

There are ways how the Federal Reserve could reduce the demand for bank reserves. Two examples:

The Federal Reserve can create new facilities similar to the discount window. If banks can borrow reserves versus collateral from the Federal Reserve, they could keep more securities, such as USTs, on their balance sheets. It would be easier for them to swap the securities into reserves.

If USTs on banks’ balance sheets would be exempt from the supplementary leverage ratio (SLR), banks would be incentivised to hold more securities on their balance sheet. Essentially, banks would not be punished for holding USTs. That could also lower the demand for bank reserves.

I hope you enjoyed this article. It might seem like a niche topic, but banking regulation is driving how banks operate, which in turn impacts money flows. Banking regulation also heavily influences repo markets, which impact bond markets. And you really want to know what is happening in bond markets because if bond markets speak, all other markets listen.

As Bill Clinton’s chief strategist James Carville famously said: “I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the President or the Pope or as a .400 baseball hitter. But now I would want to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

Very interesting to read. Thanks!

<quote>The Federal Reserve can create new facilities similar to the discount window. If banks can borrow reserves versus collateral from the Federal Reserve, they could keep more securities, such as USTs, on their balance sheets. It would be easier for them to swap the securities into reserves.</quote> <<< the facility mentioned in this quote is SRF (Standard Repo Facility). Right?

Very interesting. Thanks!